Washington State is planning to remove Steller sea lions from Washington's state list of threatened species, where they have been since 1993. The Eastern DPS (distinct population segment) of Stellers includes the population living along the west coast of North America from Southeast Alaska to central California. The population has recovered from an estimated 18,313 animals in 1979 to over 70,000 animals in 2010. Individuals, primarily males, can usually be found in the Salish Sea between September and May.

The Eastern DPS was de-listed from the US federal list of endangered species in December 2013.

The comment period for this action by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife ends on December 11, 2014.

You may submit comments by email to TandEpubliccom@dfw.wa.gov or by mail to:

Listing and Recovery Section Manager, Wildlife Program

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

600 Capitol Way

North Olympia, WA 98501-1091

Read the complete status review at the WDFW website.

Here is the Executive Summary from the document:

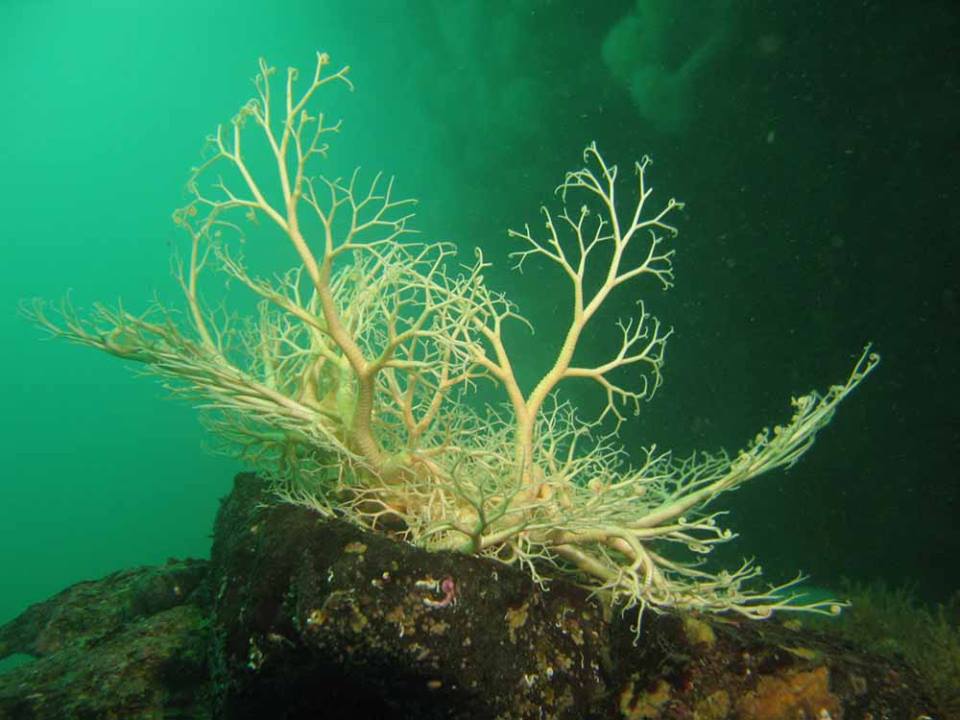

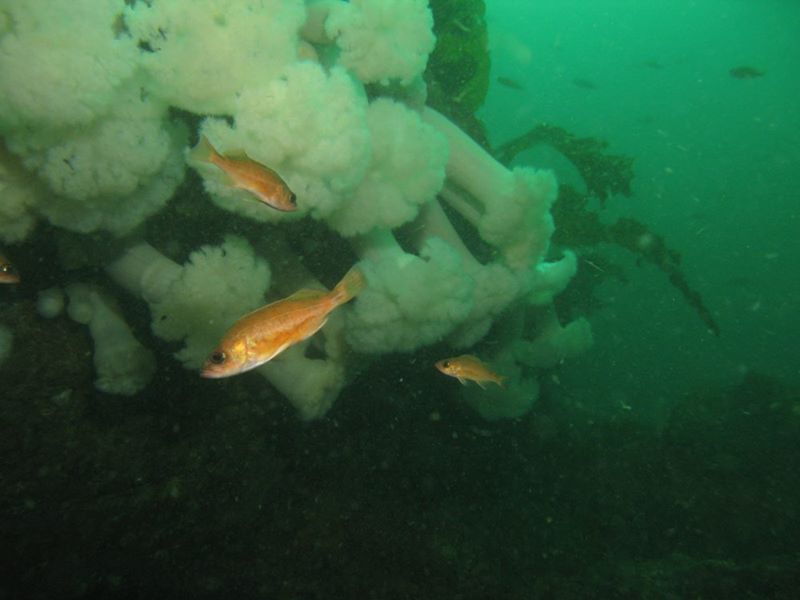

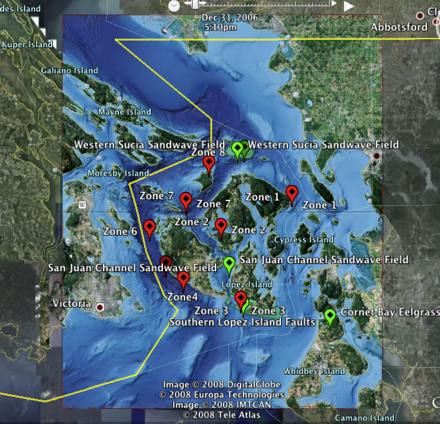

Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) in Washington belong to the eastern distinct population segment (DPS), which is one of two DPSs comprising the species. The eastern DPS ranges along the west coast of North America from Southeast Alaska to central California (i.e., east of 144°W longitude). Most Steller sea lions migrate to rookeries on islands and offshore rocks for breeding and pupping from May to August. At the rookeries, adult males defend breeding territories and compete for females; pups are born from late May to early July. Steller sea lions are dietary generalists that feed on a variety of prey. Prey commonly eaten in Washington include Pacific hake, rockfish, skates, flounders, herring, salmon, smelt, shad, and cod; white sturgeon are among the species eaten in the Columbia River. Seasonal concentrations of prey are commonly targeted. Most foraging occurs within 60 km of land and foraging trips are interspersed with regular visits to onshore resting sites known as haulouts. Haulouts in Washington are preferentially located on islands with rocky shorelines and wave-cut platforms, but cobble beaches and human-made structures such as jetties, navigational buoys, docks, and log booms are also used.

The eastern DPS, including the Steller sea lions found in Washington, experienced a major decline in abundance through much of the 1900s due primarily to human control efforts. Protections implemented during and after the 1970s against deliberate killing and other threats reversed this trend and have resulted in a period of sustained population growth. From 1979 to 2010, numbers of non-pups (individuals ≥1 year of age) and pups in the eastern DPS increased at average annual rates of 2.99% and 4.18%, respectively, with the overall population growing from an estimated 18,313 animals to 70,174 animals. Steller sea lion abundance in Washington has also grown, with numbers of non-pups at four sites used for trend analysis increasing at an average annual rate of 9.13% from 1989 to 2013. Abundance in the state peaks during the non-breeding season at roughly 2,000-2,500 animals. Most animals occur along the outer coast, with smaller numbers visiting the inner marine waters. Washington does not support any recognized rookeries (defined as having >50 pups born per year). Pupping did not occur in the state during most of the 20th century, however, small but increasing numbers of pups have been born at several sites since 1992, with a total of 60 tallied in 2014. Therefore, nearly all animals visiting Washington are born at rookeries in other states and British Columbia. Twenty-two haulouts are currently known in Washington. Additionally, major haulouts at the mouth of the Columbia River (Oregon) and along southern Vancouver Island and in the Strait of Georgia (British Columbia) are located close to the state’s waters.

The eastern DPS and Steller sea lion numbers in Washington are expected to continue increasing in the near future until eventually reaching carrying capacity with available prey resources. Sustained population growth and lack of significant threats resulted in federal delisting of the eastern DPS in December 2013. The eastern DPS may be adversely impacted by a number of known or potential human-related factors, including climate change, reduced prey abundance through competition with fisheries, human disturbance, incidental take in fishing gear, entanglement in marine debris, intentional killing, environmental contaminants, oil spills, diseases and parasites, and harmful algal blooms. An important future concern is that altered ocean conditions resulting from climate change may reduce prey availability for the species. Despite the existence of these potential adverse factors, the population has successfully recovered during the past few decades.

For these reasons, the Department recommends that Steller sea lions be delisted at the state level in Washington. If delisting occurs, the species will continue to receive protection through the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act and through its classification as a “protected wildlife” species under state law. However, delisting could lead to the future lethal removal of small numbers of individuals at locations where authorized by federal and state law.